The French burdened the Vietnamese with an extensive taxation system. This included income tax on wages, a poll tax on all adult males, stamp duties on a wide range of publications and documents, and imposts on the weighing and measuring of agricultural goods.

Even more lucrative were the state monopolies on rice wine and salt – commodities used extensively by locals. Most Vietnamese had previously made their own rice wine and gathered their own salt – but by the start of the 1900s, both could only be purchased through French outlets at heavily inflated prices.

French officials and colonists also benefited from growing, selling and exporting opium, a narcotic drug extracted from poppies. The land was set aside to grow opium poppies and by the 1930s, Vietnam was producing more than 80 tonnes of opium each year. Not only were local sales of opium very profitable, its addictiveness and stupefying effects were a useful form of social control.

By 1935, France’s collective sales of rice wine, salt and opium were earning more than 600 million francs per annum, the equivalent of $US5 billion today.

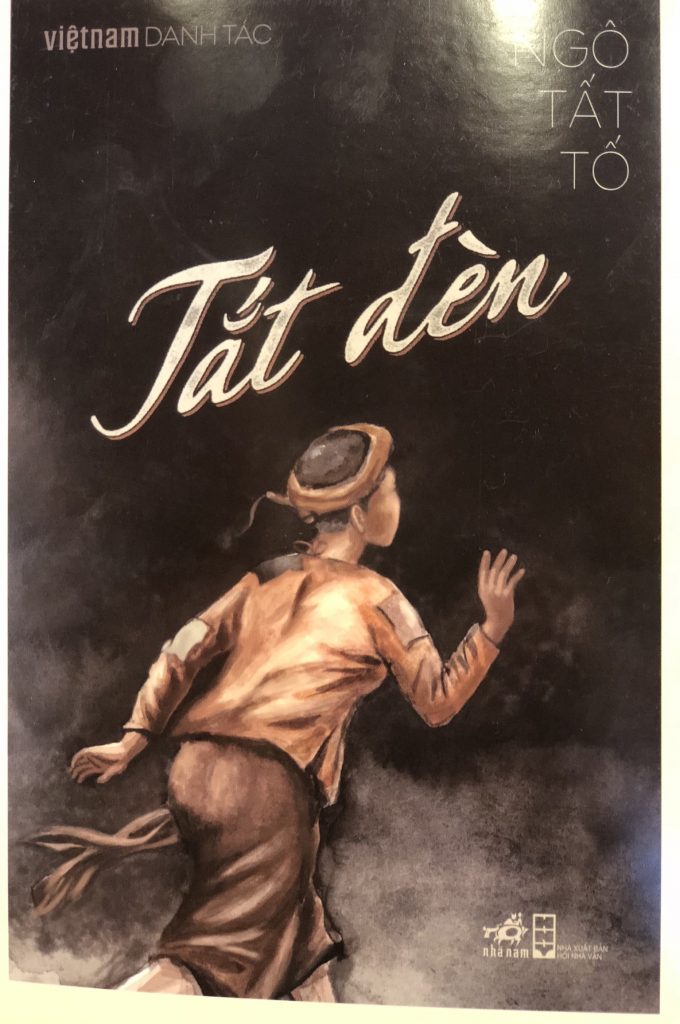

The French established rubber plantations and coal mines with Vietnamese workers virtually enslaved, and the colonial administration used corvée labor–forcing peasants to work on public projects like roads or bridges in place of paying taxes–to build up the infrastructure. In a short story by the Vietnamese writer Ngo Tat To, he illustrates the burdens of life under the French and their Vietnamese lackeys. A woman, Mrs. Dau, travels to the home of Representative Que, a collaborator with the French, to negotiate the release of her husband from prison, where he had been sent for not being able to pay his “body tax.” In exchange for Mr. Dau’s freedom, his wife is forced to trade four valuable puppies, and, tragically, her daughter Ty. Adding insult to injury, before gaining her husband’s release, she also has to pay a body tax for her brother-in-law, even though he had died months earlier. On her way out, Mrs. Dau’s fine is increased because she had paid in coin, not paper currency, and there was a “transfer fee” as well.

Ngo Tat To’s story not only reveals the colonial administration established by the French, but also the role of the Vietnamese upper classes who worked with the Europeans to exploit their own people. To the Vietnamese, those countrymen, usually large landholders and converts to Catholicism, were a threat to national sovereignty. Nationalists might refer to a collaborator as a “God-cursed traitor who acted like a worm in one’s bones,” while Court officials were “cowards excessively anxious to save their lives.” Court officials were “cowards excessively anxious to save their lives.”